The history of Libya under Muammar Gaddafi

**************************************

spanned a period of over four decades from 1969 to 2011. Gaddafi became the de facto leader of the country on 1 September 1969 after leading a group of young Libyan military officers against King Idris I in a bloodless coup d'état. After the king had fled the country, the Libyan Revolutionary Command Council

(RCC) headed by Gaddafi abolished the monarchy and the old constitution

and proclaimed the new Libyan African Republic, with the motto

"freedom, socialism, and unity".

After coming to power, the RCC government initiated a process of

directing funds toward providing education, health care and housing for

all. Despite the

reforms not being entirely effective, public education

in the country became free and primary education compulsory for both

sexes. Medical care became available to the public at no cost but

providing housing for all was a task the RCC government was not able to

complete. Under Gaddafi, per capita income in the country rose to more than US $11,000, the fifth highest in Africa. The increase in prosperity was accompanied by a controversial foreign policy, with increased political repression at home.

The name of the country was changed several times during Gaddafi's tenure as the leader. At first, the name was the Libyan Arab Republic. In 1977, the name was changed to Socialist People's Libyan Arab Jamahiriya, where Jamahiriya is a term coined by Gaddafi, usually translated as "state of the masses". The country was renamed again in 1986 to the Great Socialist People's Libyan Arab Jamahiriya. During the 1980s and 1990s, Gaddafi openly supported independence movements like Nelson Mandela's African National Congress, the Palestine Liberation Organization, the Irish Republican Army and the Polisario Front (Western Sahara), which led to a deterioration of Libya's foreign relations with several countries and that culminated in the US bombing of Libya in 1986. After the 9/11 attacks, however, the relations were mostly normalised.

In early 2011, a civil war broke out in the context of the wider "Arab Spring". The anti-Gaddafi forces formed a committee named the National Transitional Council,

on 27 February 2011. It was meant to act as an interim authority in the

rebel-controlled areas. After a number of atrocities were committed by

the government, with the threat of further bloodshed,[8] a multinational coalition led by NATO forces intervened on 21 March 2011 with the aim to protect civilians against attacks by the government's forces.[9] At the same time, the International Criminal Court issued an arrest warrant against Gaddafi and his entourage on 27 June 2011. Gaddafi was ousted from power in the wake of the fall of Tripoli

to the rebel forces on 20 August 2011, although pockets of resistance

held by forces loyal to Gaddafi's government held out for another two

months, especially in Gaddafi's hometown of Sirte, which he declared the new capital of Libya on 1 September 2011.

The fall of the last remaining cities under pro-Gaddafi control and

Sirte's capture on 20 October 2011, followed by the subsequent killing of Gaddafi, marked the end of the Libyan Arab Jamahiriya.

The discovery of significant oil reserves in 1959 and the subsequent income from petroleum sales enabled the Kingdom of Libya

to transition from one of the world's poorest nations to a wealthy

state. Although oil drastically improved the Libyan government's

finances, resentment began to build over the increased concentration of

the nation's wealth in the hands of King Idris. This discontent mounted

with the rise of Nasserism and Arab nationalism/socialism throughout North Africa and the Middle East.

On 1 September 1969, a group of about 70 young army officers known as

the Free Officers Movement and enlisted men mostly assigned to the Signal Corps, seized control of the government and in a stroke abolished the Libyan monarchy. The coup was launched at Benghazi,

and within two hours the takeover was completed. Army units quickly

rallied in support of the coup, and within a few days firmly established

military control in Tripoli and elsewhere throughout the country.

Popular reception of the coup, especially by younger people in the urban

areas, was enthusiastic. Fears of resistance in Cyrenaica and Fezzan proved unfounded. No deaths or violent incidents related to the coup were reported.

The Free Officers Movement, which claimed credit for carrying out the

coup, was headed by a twelve-member directorate that designated itself

the Revolutionary Command Council (RCC). This body constituted the

Libyan government after the coup. In its initial proclamation on 1

September, the RCC declared the country to be a free and sovereign state called the Libyan Arab Republic,

which would proceed "in the path of freedom, unity, and social justice,

guaranteeing the right of equality to its citizens, and opening before

them the doors of honorable work." The rule of the Turks and Italians

and the "reactionary" government just overthrown were characterized as

belonging to "dark ages", from which the Libyan people were called to

move forward as "free brothers" to a new age of prosperity, equality,

and honor.

The RCC advised diplomatic representatives in Libya that the

revolutionary changes had not been directed from outside the country,

that existing treaties and agreements would remain in effect, and that

foreign lives and property would be protected. Diplomatic recognition of

the new government came quickly from countries throughout the world.

United States recognition was officially extended on 6 September.

In view of the lack of internal resistance, it appeared that the

chief danger to the new government lay in the possibility of a reaction

inspired by the absent King Idris or his designated heir, Hasan ar Rida,

who had been taken into custody at the time of the coup along with

other senior civil and military officials of the royal government.

Within days of the coup, however, Hasan publicly renounced all rights to

the throne, stated his support for the new government, and called on

the people to accept it without violence. Idris, in an exchange of

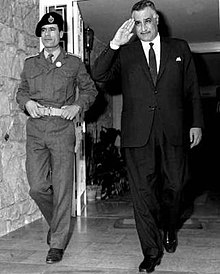

messages with the RCC through Egypt's President Nasser,

dissociated himself from reported attempts to secure British

intervention and disclaimed any intention of coming back to Libya. In

return, he was assured by the RCC of the safety of his family still in

the country. At his own request and with Nasser's approval, Idris took

up residence once again in Egypt, where he had spent his first exile and

where he remained until his death in 1983.

On 7 September 1969, the RCC announced that it had appointed a

cabinet to conduct the government of the new republic. An

American-educated technician, Mahmud Sulayman al-Maghribi,

who had been imprisoned since 1967 for his political activities, was

designated prime minister. He presided over the eight-member Council of

Ministers, of whom six, like Maghrabi, were civilians and two – Adam Said Hawwaz and Musa Ahmad

– were military officers. Neither of the officers was a member of the

RCC. The Council of Ministers was instructed to "implement the state's

general policy as drawn up by the RCC", leaving no doubt where ultimate

authority rested. The next day the RCC decided to promote Captain

Gaddafi to colonel and to appoint him commander in chief of the Libyan

Armed Forces. Although RCC spokesmen declined until January 1970 to

reveal any other names of RCC members, it was apparent from that date

onward that the head of the RCC and new de facto head of state was Gaddafi.

Analysts were quick to point out the striking similarities between

the Libyan military coup of 1969 and that in Egypt under Nasser in 1952,

and it became clear that the Egyptian experience and the charismatic

figure of Nasser had formed the model for the Free Officers Movement. As

the RCC in the last months of 1969 moved vigorously to institute

domestic reforms, it proclaimed neutrality in the confrontation between

the superpowers and opposition to all forms of colonialism and

"imperialism". It also made clear Libya's dedication to Arab unity and

to the support of the Palestinian cause against Israel. The RCC

reaffirmed the country's identity as part of the "Arab nation" and its

state religion as Islam.

It abolished parliamentary institutions, all legislative functions

being assumed by the RCC, and continued the prohibition against

political parties, in effect since 1952. The new government

categorically rejected communism – in large part because it was atheist

– and officially espoused an Arab interpretation of socialism that

integrated Islamic principles with social, economic, and political

reform. Libya had shifted, virtually overnight, from the camp of

conservative Arab traditionalist states to that of the radical

nationalist states.

THIS IS WHAT I HAVE GOT SO FAR,AND PERSONALLY I CAN'T SAY THE GUY WAS BAD TO LIBYA!!

......MAY BE,TO BE CONTINUED!!!